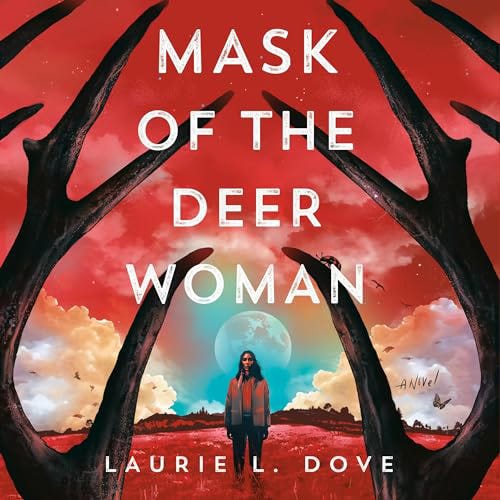

Book Review: ‘Mask Of The Deer Woman'

Chasing The Ghosts Of Missing And Murdered Indigenous Women

By Katherine Xiong

The premise of Laurie L. Dove’s debut novel “Mask of the Deer Woman” promises drama and intrigue. Its protagonist Carrie Starr, a hard-drinking detective with a tragic backstory, has recently become Tribal Marshal at the (fictional) Saliquaw Reservation where her father grew up.

Starr seeks to close the many cold cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women (a 2016 report by the The National Institute of Justice indicates that more than 80% of Native Americans have experienced violence), but police indifference and other systemic failures make her difficult job nearly impossible. She writes:

It was part of what made tracing the disappearances of Indigenous women so difficult; it could be days, even weeks, before they were truly missed. Then a quandary: where to report them missing? Until Starr’s arrival, there hadn’t been a tribal police presence for years.

As tribal numbers had dwindled on this reservation, the lack of on-site law enforcement created a gap that local agencies couldn’t fill, and they were quick to blame alcohol or drugs, runaways, sometimes prostitution.

Even when a missing woman from the rez had last been seen in the county, the sheriff’s office simply countered that the reservation was not their jurisdiction and did nothing at all.

Dove, an award-winning journalist, seems an ideal candidate to dramatize such a shocking injustice surrounding Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW). That said, “Mask of the Deer Woman’s” early chapters stray from the high-stakes police procedural narrative as Dove diverts the reader’s attention to showcase her character’s flaws.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Media Room - The Arts in Real Life to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.